When describing her district’s process for approaching how they were going to do strategic planning differently, Kelly Coffin kept bringing it back to the people.

“It’s very important that those closest to the work are those setting the direction,” said Coffin, assistant superintendent of innovation and strategic initiatives at Farmington Public Schools in Michigan.

Instead of a traditional hierarchical approach, stakeholders from throughout the learning community were invited into the district’s strategic planning process – from students and educators to community members and parents. While the district has a mission and a vision for what they want, Coffin stresses that “those closest to the work know where we need to start, and they have the credibility with the community to move it forward.”

Rosheen Hunter, a fifth-grade teacher in the district, can clearly illustrate the difference between what Farmington is doing now versus how things have been rolled out in the past.

“For past initiatives, I wasn’t as involved. I was just given a binder and told, ‘We’re starting this.’ All the teachers, we felt like we had no say in what happened – and it’s so different this time,” said Hunter, who is in her 25th year of teaching and serves on the teaching and learning committee. “Our groups are diverse. My committee includes parents, community members and high school students. I like that it’s people who are with the kids all the time. When reaching out to get people on my team, I can say that I’m the co-leader and you’ll be working with me. That’s been exciting for teachers.”

Providing a way for meaningful engagement for everyone is part of the district’s work to create a culture of equity and innovation – and to be clear about what they mean when they’re talking about it.

“We’re doing a lot of work as a community to understand what we mean by equity and innovation to try to develop a common understanding,” said Coffin. “We’ve done a lot of work historically in Farmington around equity, but if people misunderstand the information, or compartmentalize it, we can justify staying the same.”

Because staying the same isn’t an option. Serving some learners well but not others, hearing from the same stakeholders instead of finding ways to include all voices, not challenging the way things are done because that’s the way they’ve always been done – none of these are options. Not for districts like Farmington Public Schools and not for KnowledgeWorks. We’re a learning organization that supports learning organizations in their work to create systems of teaching and learning that are equitable and student-centered.

And lately, we’ve been learning a lot.

Rethinking learner profiles in support of more human-centered classrooms

Learner profiles – a snapshot of student strengths and challenges, their interests, passions and aspirations – are one of the many tools we encourage educators to co-create with their students. They’re a way to help students and teachers gain a greater understanding of a learner’s strengths, what they’re passionate about and where they may need more support.

But they’re also a place where our own biases and expectations impact the process.

Dr. Akuoma Nwadike, president of Inclusivity Education, recently partnered with KnowledgeWorks to facilitate conversations with our Leading Change Professional Learning Community to help rethink the way we use learner profiles.

“How do we address bias in what a learner profile does, or how it is upholding some of the same detriments – telling students what they are or aren’t,” said Dr. Akuoma. “We need the context behind some of these things. It’s not just an inventory.”

How can you get started co-creating learner profiles in your classroom?

Start here >

It is vital to layer questions of how a teacher’s identity and biases can come into play in the classroom on top of the traditional learner profile process in order to create a space where students feel comfortable bringing their whole selves. It’s not just about uncovering students’ interests. It’s about the why behind those interests and how their experiences have shaped how they answer these kinds of questions. For Dr. Akuoma, that’s a critical consideration – especially if there is a disparity between an educator’s experiences and their student’s experiences.

“If your students are not members of a dominant cultural identity, ask yourselves, are your students showing up as themselves or the version of them that they think the teacher wants? What is it about my students that I’ve never really asked before to get at their authentic selves?”

Dr. Akuoma stressed during the sessions that students who are not a part of a dominant cultural identity have learned what is and is not accepted or expected. Considerations of diversity and identity, for both educators and learners, are necessary for students to be able to bring their whole selves into the classroom.

A variety of strategies to refine the learner profile process in support of more equitable and student-centered learning environments were surfaced during the sessions. These included:

- Providing educators with a balanced schedule that allowed for engaging with students at community events, sporting events or with extracurriculars, where they might have the opportunity to see another side of their learners

- Building robust advisory programs for students and teachers to connect and engage in critical conversations

- Creating meaningful platforms for student engagement that can be acted upon, rather than just collected

- Being clear about how learner profiles will be used to inform curriculum and instruction

- Intentionally choosing meeting places that do not reinforce a power dynamic but instead place educators and learners on equal footing

“It’s about taking a listening stance rather than a talking stance,” said Eric Brooks, chief academic officer with Yuma Union High School District in Arizona, speaking not just of the learner profile itself but in how it is designed and executed. “We need student voices not just heard in the gathering but heard throughout the process. How do we do that with students who aren’t used to living in worlds where they are being asked questions like that? It sounds good for us; we’re constantly having to reimagine and being provided opportunities. But if students don’t have our backgrounds, if they don’t come to the table with those same kinds of experiences, how do we make it easy for them to access those ideas?”

How could learner profiles mitigate bias and capture individual identity? Check out one of the videos from the Leading Change Professional Community “Rethinking Learner Profiles” workshop series.

Watch now >

For Dr. Akuoma, the work will always be centered in whatever it takes to see the student as an individual, a whole person.

“Personalization requires you to see the humanity in your students,” Dr. Akuoma said. “They’re not just students, they’re people. ‘Student’ is just a role they have. You have to take the time to explore how identity shows up in classrooms because of who that person is outside of the classroom.”

Pursuing data equity and the democratization of data

How we think about and use data is another area where unintentional biases may come into play – and a place where we recognize an opportunity to do better.

“With data equity, there are at least two fundamental questions we’re asking: For what, and for whom,” said Gregory Seaton, senior director of impact and improvement at KnowledgeWorks. “One of the things we’ve worked hard on is thinking about how we engage local stakeholders in the framing, collection and interpretation of the data that we’re seeing.”

Personalization requires you to see the humanity in your students. They’re not just students, they’re people. “Student” is just a role they have.

Understanding researcher positionality – what Eric Toshalis, senior director of strategic initiatives at KnowledgeWorks, describes as “recognizing that people from dominant backgrounds tend to use dominant funds of knowledge and forms of inquiry to reproduce dominant interpretations of data” – is critical to the democratization of data and research. It’s not unlike what happens between teachers and students when they’re co-creating learner profiles.

“No matter who you are, you’re bringing lenses and biases into the work. We are asking ourselves and our research partners to surface those deeper questions,” said Rebecca Wolfe, vice president of impact and improvement at KnowledgeWorks. “Researchers have to think and reflect on who they are and where they stand, as they can bring in an unequal power dynamic.”

Seaton and Wolfe both cite how disaggregating data by demographic is just the first step in thinking about data equity.

“Most of the time when you see data collected, particularly in equity-based education research, it boils all the data down to comparisons by race, gender or class,” said Seaton. “Baked into that thinking is that whatever you are – whether it’s female, Asian-American, economically-disadvantaged or of differing abilities – being a part of that demographic is what leads to the outcomes. But it’s really important to understand the role that context and experience plays, and how we capture that in the data to move beyond simple comparisons.”

Wolfe adds that “democratizing data means we don’t just look at the numbers. We have to think about how to present the numbers in ways that are the most useful and actionable, that consider context and outcomes, and work toward continuous improvement.”

Among the strategies KnowledgeWorks is employing in our pursuit of data equity and the democratization of data are:

- Embedding data fellows within our learning communities who can make connections between research and practice within a local context

- Being intentional with language; for example, not describing disaggregating data by “subgroup,” which suggests that there is a dominant group that all others are trying to be like

- Finding a balance between making data available quickly for partners to use while also building trust with partners to ensure the data is meaningful and useful

- Taking special care with how data and stories are shared when the end group size is small enough to be identifiable

- Employing a mixed-method approach to data to avoid the perception that quantitative data is superior to other kinds of data

Casey Collins is the educational equity coordinator at West Fargo Public Schools in North Dakota, one of four districts involved in the North Dakota Personalized, Competency-Based Learning Initiative. Collins helps to lead the district’s equity task force – and how they collect and use data.

“We have a tremendous amount of data, but how are we making meaning of it to make change? Whether it’s data indicating an achievement gap or something else, how are we really making meaning of it and doing something with it? We want to zoom in,” said Collins, stressing the district’s interest in meaningful student data, specifically in how they might better serve students who haven’t been served well in the past.

Three years in to supporting four North Dakota school districts in advancing student-centered learning practices as part of the North Dakota Personalized, Competency-Based Learning Initiative, here’s what we’ve learned: Read more >

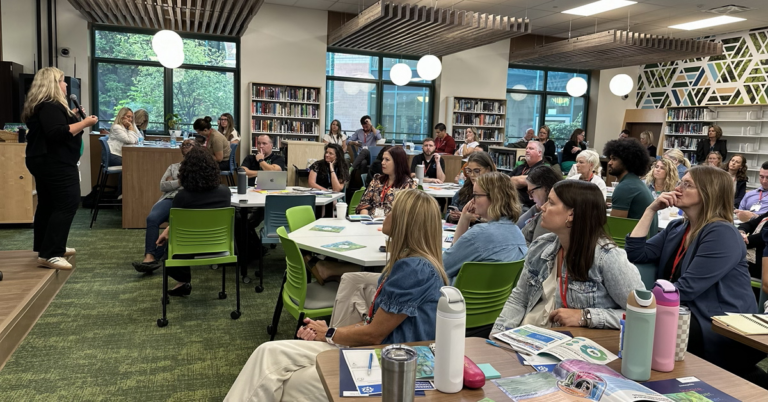

During committee meetings, the task force surfaces guiding questions related to curriculum and instruction, data analysis, grading practices and others. But the goal, according to Collins, isn’t about the district sharing out. It’s about the opportunity to take data in.

“The true purpose of the task force is to bring in diverse voices – from students and parents, to community members that are interested,” Collins said. “Even the way the time is balanced during meetings, we have 20 – 30 minutes for giving information and an hour for getting information. It prioritizes what we’re trying to capture. We have consistent facilitators that can get to know a small group. Their conversations have gotten deeper over time.”

For West Fargo and for KnowledgeWorks, the numbers are just a part of the story. They aren’t the whole story.

“What our students are experiencing in the classroom by groups is a totally different question than what are the outcomes by groups,” Seaton said. “Once we begin to understand experiences, we can think about strategies, interventions and ways of adding more supports to promote better and more equitable outcomes for students.”

Once we begin to understand experiences, we can think about strategies, interventions and ways of adding more supports to promote better and more equitable outcomes for students.

Aligning our practices to our commitments

Our navigation tool, Finding Your Path: A Navigation Tool for Scaling Personalized, Competency-Based Learning, is critical in our work with schools and districts. Designed to help learning communities understand the conditions for sustainable systems change and to develop and advance a strategic plan for district-wide transformation to personalized, competency-based learning, the most recent version of the tool centered equity in a way that the previous version hadn’t been as intentional about.

And the alignment process was about looking at specific strategies and practices and taking it a step further.

“While we have long believed that personalized, competency-based learning can best support all students, we hadn’t been as explicit as we wanted to be about how that happens,” said Lauren McCauley, senior director of teaching and learning at KnowledgeWorks, of recent work to create alignment between the navigation tool and organizational commitments to diversity, equity, inclusion and justice. “The way that we design our supports, the way we respond to what we’re hearing from the field, the better able we are to get to that end. This process has helped crystallize for us that personalized, competency-based learning is not the end – having a more equitable, diverse, just system is the end.”

Some of the examples of alignment between our 10 district conditions – the essential elements for successfully scaling personalized learning district-wide, based on in-depth research with districts across the country – and our commitment to equitable outcomes they uncovered included:

- Learning community members have agency and can speak to and believe in their role in making a collective impact

- Curriculum is accessible, transparent and clear to all relevant stakeholders within the learning community

- Learning communities create flexible learning environments that support the “whole learner,” which includes students and educators

“Doing this kind of intentional alignment keeps our diversity, equity, inclusion and justice work from being siloed. It helps make it actionable,” said Syd Young, director of teaching and learning at KnowledgeWorks. “It’s like knowing and doing with classroom standards. Something’s been taught or learned, but it’s about applying those values.”

This process has helped crystallize for us that personalized, competency-based learning is not the end – having a more equitable, diverse, just system is the end.

Both Young and McCauley also cite how having these conversations internally helps to better facilitate them in the learner communities we serve. When words like “equity” and “inclusion” are being misunderstood or weaponized, being clear about what the work truly looks like is more important than ever. We remain committed to personalized, competency-based learning as a way to realize access and opportunity for each learner no matter their race, income or ability.

To do this, we must continue to educate ourselves.

Embracing our responsibility

Awareness and alignment is at the heart of the work in Farmington, too.

“As a bilingual learner, I spoke very little English when I started school,” said Hunter. “I have a heart for my ELL kids, my Black kids. I see that they’re misrepresented. This is my 25th year; I’ve seen a lot. A lot of our curriculum needs to change, so when I saw the opportunity to be on the committee to do it, I wanted in.”

We’re in this with the people we serve – and for the students who are counting on us to do better, to do our best.

Understand the conditions for systems change to help your learning community scale personalized, competency-based learning.

This was written by former Senior Manager of Communications Jillian Kuhlmann.

Understand the conditions for systems change to help your learning community scale personalized, competency-based learning with Finding Your Path: A Navigation Tool for Scaling Personalized, Competency-Based Learning.

Understand the conditions for systems change to help your learning community scale personalized, competency-based learning with Finding Your Path: A Navigation Tool for Scaling Personalized, Competency-Based Learning.