While personalized learning can exist at the classroom-level, competency-based education is a systemic approach to ensuring personalization across a state or district. Through research with districts across the country who are working to scale personalized, competency-based learning systems, KnowledgeWorks has learned that to effectively move systemic transformation forward, learning communities must prioritize work on their shared vision; learning community culture; collective and individual agency; and transparency.

Marysville Exempted Village School District in Marysville, Ohio, with whom KnowledgeWorks began work in 2013, is one of the learning communities we’ve learned from and one whose journey illustrates what it can look like to commit to the success of each learner.

When she became superintendent of Marysville Exempted Village School District in 2013, one of Diane Mankins’ first acts was to hold more than 20 community meetings that were open to parents, educators, community leaders and stakeholders. She had two questions for attendees: What are you most proud of in our schools? And if you could wave a magic wand and change one thing, what would it be?

Mankins shared that those conversations drove changes to innovate the district. She found the positive feedback as informative as the areas community members and school leaders identified for improvement. While many shared their impressions of a safe, purposeful school with good academic performance, there was also a desire to foster stronger relationships with local businesses, to address a workforce gap and to look more closely at what the district could do for every student, rather than just “all” students.

Through research with districts across the country who are working to scale personalized learning systems, KnowledgeWorks has identified 12 conditions that must be refined and aligned toward the shared vision for teaching and learning. Learn More »

Building a shared vision that serves every learners

“There was no vision set for the district,” Mankins explained. “There was this sense that we had good teachers, good kids, that everybody was working really hard, but our arrows were all pointing in different directions.”

By creating a shared vision, each person invested in the school district and community can make progress, together.

Following community forums, Mankins convened a design team, which included individuals from the district and from within the community, to begin crafting what she saw as a much-needed vision for the future of Marysville schools: meeting the needs of every student through personalized learning.

Motivated by that vision, the district applied for a grant from the state of Ohio, which they used in part to design and open a STEM-focused, mastery-based early college high school in partnership with Columbus State Community College. By expanding on that school’s success and utilizing a personalized, competency-based approach across the district, students of all ages began to develop the essential habits of mind necessary for success in high school, college and career: growth mindset, time management, self-control and taking the initiative and learning to ask for help.

The role of community in creating a shared vision

It is critical for community partners to be involved from the beginning in the visioning process. In Marysville, Ohio, community members were able to help with the creation and execution of a vision for personalized learning, as well sharing workforce development needs, ensuring that Marysville graduates had a reason – and the desire – to stay and contribute to the community.

Fostering a strong culture

In a personalized, competency-based system, culture is built on relationships and sustained around expectations of innovative mindsets, inclusivity, celebrations of growth and continuous improvement at all levels of the system.

The influence of culture is evident around every turn in Navin Elementary School in Marysville.

“The culture here has always been one of family, providing safety and love to every child that walks through the door,” says Lynette Lewis, principal of Navin Elementary School. “Personalized learning has helped us to look even more at every child as an individual: how they learn best, what they care about, and what makes them excited to learn and want to be involved with their education.”

Incorporating student voice and encouraging student agency at all grade levels are essential practices in support of Marysville’s vision, and both students and teachers have benefitted from this approach.

Fostering student agency and teacher agency

Agency grows from a culture of trust that enables individuals to have a voice in achieving the shared vision of a school district. For a student, it means being able to make choices and actions to fully participate in their own learning.

Students throughout Marysville schools use their agency from small decisions, such as where they want to sit in their kindergarten classroom, to much larger decisions around shared concerns, as happens at Tri Academy.

At weekly meetings called town Tri Town Halls, the students and staff of Tri Academy meet to share objectives for the week, make plans and raise any concerns.

“Everyone has a voice,” then student Shelby Jackson shared in 2019. “Teachers take our inputs very seriously.”

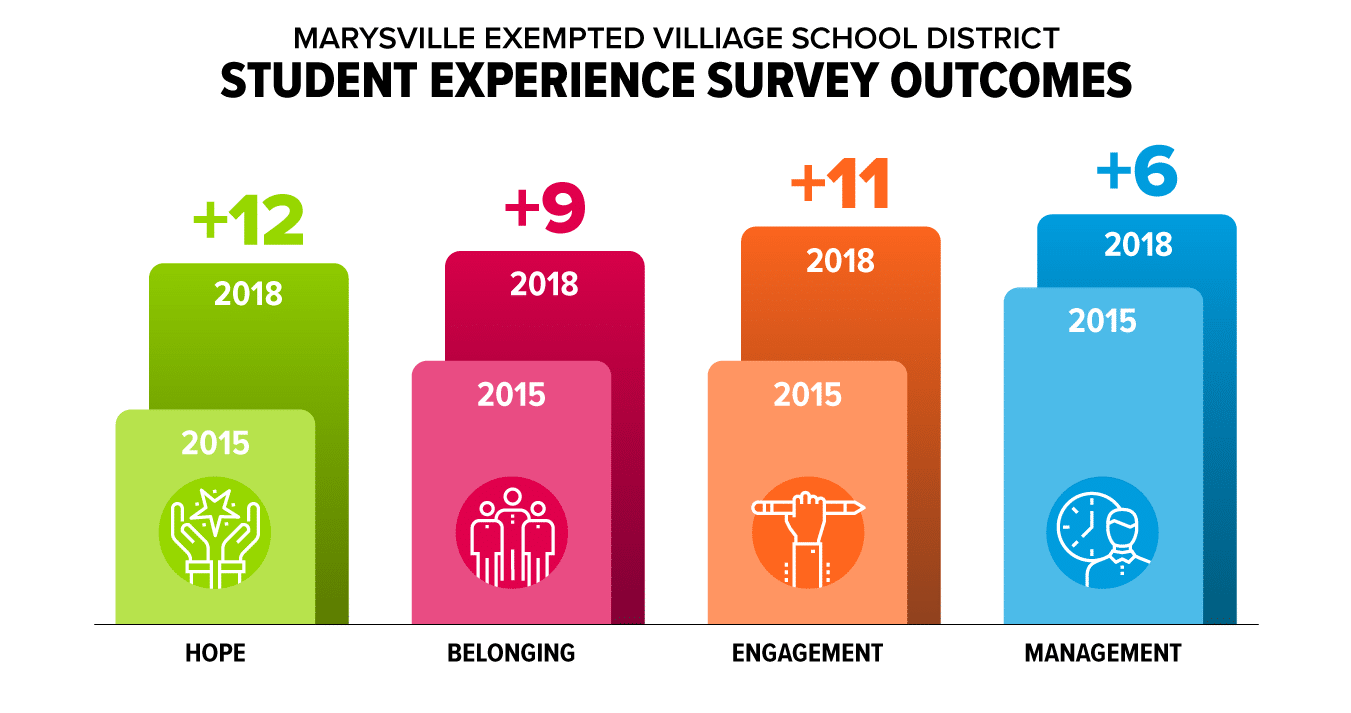

A way Marysville tracked progress for their students on topics like agency was by asking them to complete the Student Experience Survey. It tracks four metrics that traditional grades can’t capture: the degree to which students feel hopeful, engaged and able to self-manage.

In every category, students reported better results:

Transparency is key

Transparency builds inclusivity and trust through common language, shared decision-making and accountability that are visible and accessible by all members of the learning community.

For school district staff, student families and community members, being open and honest about the process of transitioning to a personalized, competency-based learning approach is one thing that helped Marysville succeed. In classrooms, transparency about learning expectations, ensuring students are aware of their learning targets and what they need to do to demonstrate mastery, is part of what creates student agency and helps the district deliver on their mission.

For Robin Kanaan, a KnowledgeWorks teaching and learning director who started working with Marysville educators in 2013, the drive in Marysville schools to see every student as “special” is remarkable.

“One of the things that I think that is so amazing in Marysville is that through the implementation of learner-centered practices, they’re meeting the needs of individual students,” said Kanaan. “It really is a systemic approach that is showing gains not only across the district but in individual schools for individual kids.”

Our navigation tool walks through the conditions necessary for sustainable systems change and how to advance a strategic plan for district-wide transformation to personalized, competency-based learning.