While site visits are a part of the learning that takes place for many schools and districts moving toward personalized, competency-based learning, three districts in three different states wanted to make it easier to share what they’ve learned and scale student-centered practices within their own learning communities. They host personalized learning institutes that ensure their educators and staff aren’t the only ones who benefit: teachers, leaders and school board members from all over the country are welcome.

And when there’s an opportunity to learn from other districts about personalized, competency-based learning, people show up. Though they’re at different stages in their personalized learning journeys – Kettle Moraine School District in Wisconsin started the work in 2010, Northern Cass Public School District #97 in North Dakota in 2016 and Santa Cruz Valley Unified School District #35 in Arizona in 2019 – these districts are building momentum for learner-centered practices and competency-based education. Part of how they’ve gotten to be where they are is by learning from each other: before hosting their own institute, educators and leaders from Northern Cass attended a personalized learning institute in Kettle Moraine, and the same was true for educators and leaders from Santa Cruz Valley, who visited both. And now Santa Cruz Valley is hosting districts.

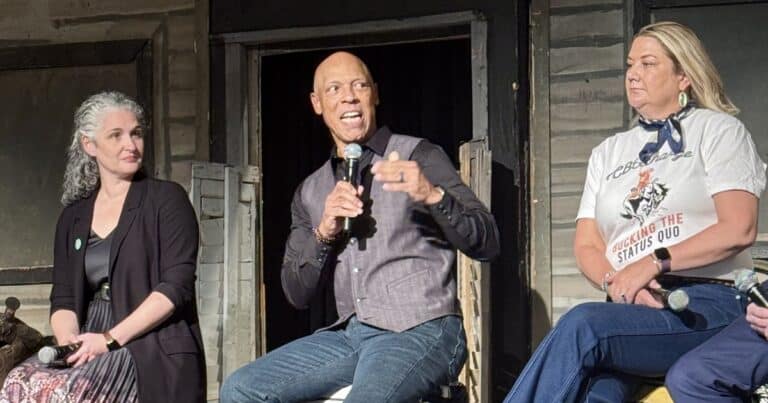

We had the opportunity to speak with Theresa Ewald, former assistance superintendent with Kettle Moraine, Cory Steiner, superintendent with Northern Cass, and Stephen Schadler, associate superintendent with Santa Cruz Valley, to learn more about the value in seeing learning approaches firsthand, peer-learning and how to make it happen in your own learning community.

Why is it important for educators to see what personalized learning looks like for themselves?

Cory Steiner: What’s probably one of the most memorable experiences kids have in their school years? Field trips. That’s exactly what we’re doing with educators. It’s a great practice. Let’s let kids go on an experiential trip outside the building and link it to learning. It’s not just about missing a day of school. It’s the same thing with adults. Hey, you’re going to miss a day of school. We’re investing in you. We’re going to have this trip and when we come back, we want to apply that learning in some way. We want to share that excitement in some way.

Stephen Schadler: The greatest value in visiting and observing learning communities is the idea that we’re all practicing. No one’s perfect yet.

What’s the value in hosting or attending a personalized learning institute?

Theresa Ewald: A lot of people were curious about what we were doing and were coming to visit. It was really getting hard for me to manage. There were hundreds of people. In 2016, I think I had 500 people visiting during the school year.

I was getting an understanding from when people came to visit that they didn’t have enough background knowledge to understand what they were looking for. People were following up with so many questions for my staff that it became burdensome, so we decided we wanted to pair professional development with the visit. What started out as a couple of hours of professional development turned into a two-day event, with one full day of classroom visits, and then one full day of professional development. We started doing that twice a year to give people a broad understanding of what we were trying to do.

There was also this amazing benefit for my staff to tell their story. When you have to tell your story, you reaffirm your commitment and your excitement.

The other advantage I saw was our ability to network and be in concert with like-minded people from across the country. When we started, there were very few games in town. Within a few years we were like, “Oh my gosh, there’s people in North Dakota, there’s people in California, there’s people in Missouri and Ohio,” and that gave us some confidence.

Cory Steiner: The people that we have met has been probably the biggest or most important thing that’s come out of hosting an institute. Now we have this group of people that we can reach out to.

Our site visits are a feedback mechanism for our district. We want to know what people see. And there’s validation. This is hard work. You’re going to take all your best practices, but you’re going to change when you use them and how you use them. You’re going to take what it feels like to probably be in your first three years of teaching and be prepared to commit to feeling that way the rest of your career if you’re truly going to personalize because this is a non-arrival practice. You never get there because whatever learners get in front of you, you have to be ready to meet them in a very specific way.

The site visits really challenge our people to live in perpetual beta. When they know that others from around the country are going to be coming in to watch, they are always trying to figure out, “What work am I doing on the edges to continually get better and to show people that I’m committed to continuous improvement?”

What advice do you have for leaders wanting to fund travel for their staff?

Cory Steiner: One of the first site visits we ever did was to Lindsay Unified School District outside of Fresno, California. They have these great learner ambassadors that are taking you on the tour, and they’re very well-spoken; they’re very honest. You’re seeing things in classrooms and you think, “Hey, we could do that.” One of the board members that was with us on the visit turned to me and said, “Is this what you’re imagining?” I said yes. And they said, “Okay, go do it. You have our support. Go do it.”

When we started our institute, we started with nothing, and we went out to donors who were interested in shifting the paradigm of learning in this country. There’s a lot of people that are very interested in that.

Maybe the person in the superintendent role is saying, “No money.” Find a way to start watching the people that are doing it in your district. Find the building that’s doing personalized learning well, find the educator in your building that’s doing personalized learning well, and say, “Well, okay, you’re not going to send me to Lindsay, California. Can I walk down to Mrs. Smith’s room and spend a half hour, 45 minutes watching her? Because she’s doing this.” And then you try to start build some momentum that way too.”

How would you describe the role that peer-to-peer educator learning plays in implementing personalized, competency-based learning?

Theresa Ewald: As educators, we have done ourselves a disservice when we talk about the science of teaching and learning and automatically go to textbooks and speakers and people who do the research. There’s art and there’s science, and our teachers have the art and the science together. Learning from each other is huge and it models what we want to see in our classrooms. You can’t expect teachers to set up a classroom to do for kids what we aren’t willing to do for teachers.

Cory Steiner: Bar none, this is the way to scale personalized, competency-based learning: by observing it and others that are exemplars, building skills and then building your professional development around what you see as the areas of strength, and where there are gaps, as well.

How have you helped educators get comfortable with being observed and getting peer feedback?

Stephen Schadler: I think that probably starts at the building level. We use the words trust and vulnerability and relationships quite often, and I remind my staff that teaching is a practice; we practice every day. Doctors practice every day, too. For whatever reason, we’re afraid to acknowledge that and we’re afraid to be imperfect. Observation and feedback are just a part of working in our district.

Cory Steiner: There is no place in our life that we’re not getting feedback, but it does seem for some reason the moment that we do say, “Hey, this could be done a little better, we could improve. Here’s some feedback,” people get defensive about that. And it’s not because I think people aren’t doing their job, it’s because we see that they have the capacity to do even more amazing work for our learners. And we know that’s why we got into teaching.

There’s no opting out of observation. Your day shouldn’t look special because we have a group coming in. This is not a dog and pony show. If they’re like, “Well, my kids are just working on backfilling standards.” Great. Talk to visitors about what that looks like because that’s going to be something everybody will need to do.

Theresa Ewald: When we first started, the directions we gave to visitors was, “You’re looking at kids, you’re not looking at the teacher.” Have people focus on what the learners are doing, and what those learners are doing that you wish your learners could be doing. What are those learners saying?

Students led our tours. They would be the ones talking about the work and what’s happening and showing you the data tools and all the things. It’s their classroom. Only one of the 30 people in a classroom is a teacher. What about the other 29 people and what they have to say? That helped a bit.

What about personalized, competency-based learning transcends region and demographics?

Theresa Ewald: One of the challenges of having a visit is people want the binder. “Can you just give us your binder and we’ll go do it?” No, because the binder here is for the kids here. You make your own binder for the kids that you’re serving now who, frankly, are going to change every couple of years anyhow. The ultimate goal is that the learner can see where they fit in the system and advocate for what they need.

Stephen Schadler: We’re in rural southern Arizona. So, when we take people to rural North Dakota or Wisconsin it just completely opens things up. When we went to the institute in Kettle Moraine, there was one point where kids were in between classes and some young man got very loud with a teacher, and another teacher came out of a room, and they had to get the situation under control. And our teachers loved that because it was like, “Okay, they have kids who are grumpy all day, just like we do.” Because prior to that, we were hearing that, “Oh, they’re higher socioeconomic status than we are, so I don’t know if this is going to work in our community.”

By taking people lots of places and seeing that the Midwest is working on this, the Northwest is working on this, the Southwest is working on this, hot climates, cold climates, rural climates, urban areas, eventually the mindset changes. We’re all in this perpetual beta state, and that’s okay.

It’s like a picture is worth a thousand words. Let one teacher visit someone else’s classroom in the middle of Wisconsin, and that saves you 1,000 words of professional development.

This was written by former Senior Manager of Communications Jillian Kuhlmann.