A student-led initiative to change Seneca Valley School District’s Indigenous mascot failed in 2000 – but this year, a new group of students succeeded.

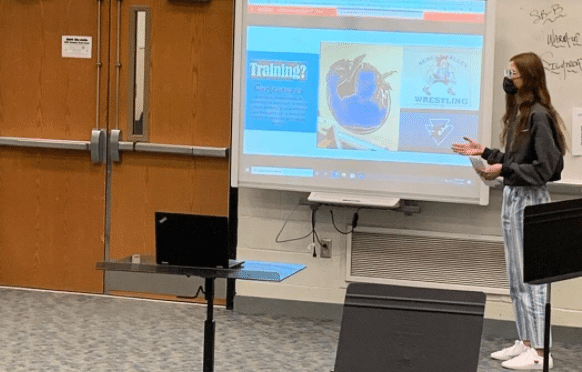

At the same time Claire McCafferty was researching and drafting mock legislation for her argument class around why their district’s mascot, a raider, was inappropriate and should be changed, Vivian Palmer was writing to the district to argue the same thing. Another student, Benaifer Sepai, had also recently invited the Seneca-Iroquois National Museum Director Dr. Joe Stahlman to speak during her senior project and the question of changing the mascot surfaced. The student diversity committee, Social Handprints Overcoming Unjust Treatment (SHOUT), brought them altogether.

“We are directly responsible to the Seneca Nation because we share their name,” said Palmer, who “jumped at the chance” to join SHOUT’s student initiative to remove Indigenous imagery from the Harmony, Pennsylvania school district, launched following Dr. Stahlman’s presentation.

Proud of their past; committed to their future

Researching the history of the district’s mascot involved combing through old yearbooks, consulting with alumni and teachers and learning from tribal websites and perspectives. They discovered that the mascot was chosen after students conducted extensive research into the history of the region in 1961.

“Those students researched, and made educated decisions based on realities at the time,” said McCafferty. “They accepted a duty to respect the culture and the wishes of the people that they undeniably represent.”

McCafferty went on in the presentation to explore how their district’s sense of duty diminished over time but is just as important today as it was then – especially as the research she and other SHOUT students were conducting illustrated that their mascot was no longer honoring the Seneca Nation.

“There was an aspect that this was happening all over the country, that mascots were being challenged, but we were able to anchor our argument in the fact that it’s a human issue – looking at our community’s history,” said McCafferty, who explained that the presentation they created for the school board focused on how the mascot was not only disrespectful and damaging to the Seneca Nation, but also reflected back on the community in a way that didn’t represent who they were and who they aspired to be. “As a school, what characteristics do we embody? Respect, dignity. We used those characteristics to help contextualize this issue. This isn’t what our school represents. Even if people don’t understand it’s offensive, it’s coming off that way.”

SHOUT members met with the district’s communications director to identify what parts of their presentation might be sensationalized in local media so, according to Palmer, they could strategize solutions and “make sure things were taken seriously.”

When Daniel Guerra, assistant principal at Seneca Valley Senior High School and one of SHOUT’s advisors, introduced SHOUT to the school board, he cited that their education has challenged them to “engage with the complex, ask deep questions and share their findings with the community.” He stressed that the work students like McCafferty and Palmer did was “ungraded and voluntary” and demonstrated work beyond a content area: how to construct an argument, how to make it accessible, strategic planning to achieve goals and having a positive influence on others.

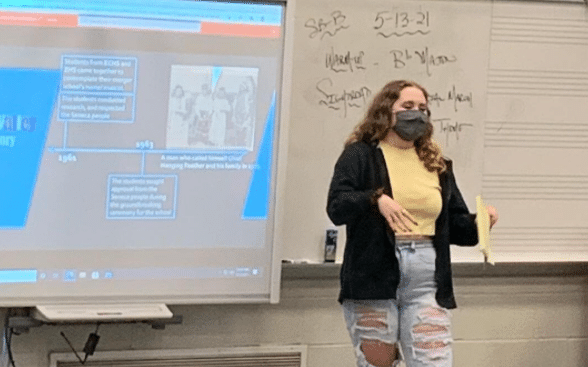

Driven by their passions and interests, Sepai put it best when she began their presentation to the board, saying “we feel it is our duty as proud Seneca Valley students to do this, considering that we are proud of our past and yet committed to our future.”

A learning experience for everyone involved

After making their case to the school board, Palmer and McCafferty worked together to build a website that showcased the presentation, making it accessible for other students and for their community – and combat some of the phony polls around Indigenous tribes feeling honored by mascots with evidence from the tribes themselves. In addition to offering an explanation and evidence for why the mascot needed to be changed, they offered voicemail and email templates for others to advocate for the Raider’s removal, too.

Palmer and McCafferty expected that they would receive some pushback from the community – and were candid about what they learned from it.

“It’s easy when you’re on a side of an issue and you’re so strong in your beliefs, but the other side is just as passionate as I am and we have to temper that passion,” said Palmer. “I learned that a lot of people who supported this mascot weren’t trying to be offensive or hurt people; they just didn’t know.”

In successive presentations with students following the school board presentation, McCafferty and Palmer explained that SHOUT provided opportunities for students to ask questions.

“Students weren’t always able to understand that something they’ve been rallying around could be harmful,” said McCafferty.

But there was a great deal of support for the initiative from teachers and students alike, and McCafferty and Palmer felt they could rely on their social circles, as well: friends who could help other friends understand where they were coming from and what they were trying to do.

And it worked.

“There’s so much more change that needs to be made.”

The school board voted unanimously in June of 2021 to retire the mascot and associated Indigenous imagery but to keep the Raider name. While SHOUT celebrated the progress made, the school board decision was galvanizing for McCafferty and Palmer. Now co-chairs of SHOUT, they began to think about how they could not only continue their efforts to educate their community about Indigenous issues, but also how they might help other students learn to advocate for the things that they care about.

“The school board decision reinforced the fact that the work is continuous,” said Palmer. “There’s so much more change that needs to be made: representation in our school curriculum for Indigenous peoples, how we teach Indigenous cultures. We need to connect our school to the Seneca Nation in a way to educate students more thoroughly. It’s not one big event. It’s continuous change.”

A SHOUT conference provided McCafferty, Palmer and others the opportunity to connect with other students in the region interested in social action. Guerra celebrates the ways their work demonstrates the learner-centered culture in Seneca Valley.

“It’s been really inspiring to see our students as advocates and see them taking ownership in the school as stakeholders and citizens, using their interests and their passions to get really deep learning experiences,” said Guerra. “I’m am looking forward to a future where projects that are human-centered and community-engaging, no matter the issue or content area, are common practice and encompass the work of all students.”

McCafferty hopes their work continues to make an impact – and not just in Seneca Valley.

“We want to make this big so that students across the country know that they have a voice, that they can spark change.”

How are communities advocating for change by centering art? Take a look at some examples and strategies to apply.

This was written by former Senior Manager of Communications Jillian Kuhlmann.