Educators who are new to student-centered practices may find it daunting to think about a classroom where learning is meaningful and relevant for each learner – exhausting themselves designing experiences tailored to appeal to learners whose interests and needs are unique and varied. While choice boards are a common and safe place to start in offering student voice and choice, choice boards that include something for everyone aren’t what offering authentic choices is really about.

A choice board or playlist where it’s the teacher’s responsibility to personalize for each learner means more exhausted educators – and learners who may not make the connection between how they learn and how they demonstrate their learning. Helping kids to understand themselves as learners, how to make choices and how to advocate for what they need, is closer to the goal.

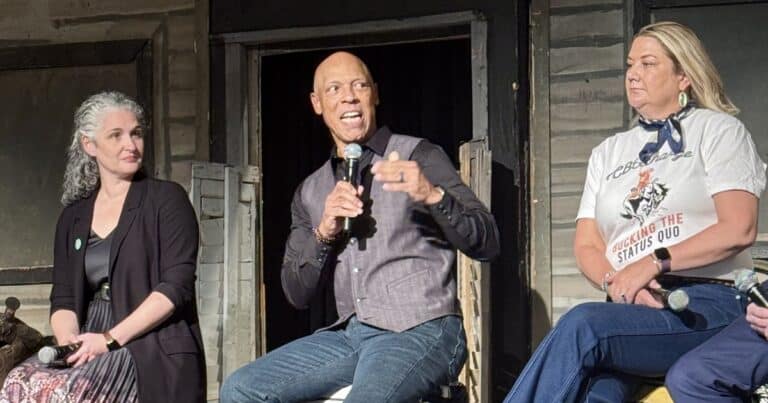

“When the educator is doing all the work, then we really aren’t getting to authentic voice and choice,” said Greg Dobitz, principal at Oakes Elementary School in Oakes, North Dakota. As part of the North Dakota Network for Personalized Learning, Dobitz and his colleagues hosted a site visit at his school for educators from other North Dakota schools. The network stresses that the site visit is as much of a learning experience for educators within the hosting school as it is for those visiting. When one of the visiting educators asked Dobitz to consider where all the choices on the choice board came from, and how they might design tasks that are broad enough to allow for authentic choice to be embedded within them, it was a real ah-ha moment for him and for his peers.

“We learn a lot about ourselves when we open ourselves up to a new set of eyes,” Dobitz said. “We have been thinking we were offering all these wonderful choices, all these things that learners could do, but it was all educator-created, educator-driven.”

How choices are scaffolded and supported is important.

Lori Phillips, director of teaching and learning with KnowledgeWorks and a former high school Biology teacher, knows it can be a challenging shift for educators to let go some of the control, but that it’s essential. Educators must feel comfortable and supported reimagining their role and shifting responsibility to learners.

“Personalized learning is not asking the educators to personalize for kids; it is asking educators to create opportunities and support kids in making learning personal for themselves,” said Phillips. Getting to know a student, their likes and dislikes, their needs and challenges, is no less important, but it’s all in service of a student-teacher relationship that supports learners in knowing themselves and feeling confident to drive their own learning. “Individualizing is not the same as personalizing. We don’t need 800 choices on a choice board so that everyone is happy.”

After the site visit, Dobitz explained that the way they approached choice boards shifted: many educators continued to generate and offer choices in one column of the choice board but also opened up a second column for kids to tell them how they wanted to demonstrate what they knew and what they could do. Dobitz stressed that beginning to offer authentic choices begins with a conversation between the teacher and the student, and that it’s a process. Not every kid is ready to make every decision but giving them opportunities to practice helps shift the classroom toward one that is student rather than teacher-driven.

“Some of our educators didn’t change a thing,” said Dobitz. “It was just the conversations that they had surrounding the choices that they were offering. It wasn’t just choose two of these tasks, it was, here are some choices but I’m not limiting you to these.”

Kathy Warren is a fourth, fifth and sixth grade social studies teacher at Oakes, and said the process of offering more choices is helping her students become more curious and inquisitive learners.

“Learners are asking quality questions. As they work to show their learning, I see creativity and critical thinking in the design process,” said Warren. “They are no longer just doing something, then asking, what’s my score? Many learners are eager to show what they know.”

Warren also highlights how offering choices provides more opportunity for her to learn what her students need. Some require more structure and more examples, while others know exactly what they want to do. And because of the conversations that happen around their learning and how they choose to demonstrate it, Warren feels she has a better understanding of what her students actually know versus what she would learn from a single assessment.

“You know more of what they know, not just how they scored on a multiple-choice test,” said Warren.

Oakes educators have the opportunity to learn from each other and share ideas about how to best implement choice boards, playlists and other ways of building student ownership of their learning. And while free choice seating and choice boards are among the first things many educators try, Warren explains that whenever she sees something she likes, she looks for ways to work it into her classroom. She stresses that it’s a process for teachers, too – changing things a little bit at a time, figuring out what works and what could be refined.

“One thing that I say a lot is that I don’t think I would ever go back to the traditional way of doing things,” Warren said. “Not that the old ways were bad, this is just so much better. I love the creativity and inspiration this is bringing out in kids. We just have to keep tweaking and making it better.”

It’s okay to make bad choices – and learn from them.

Making choices often means engaging in productive struggle. Productive struggle is another crucial part of the learning process and it can be just that – a struggle. Phillips stressed that because educators want to see their learners succeed, they try to set them up for success. But that can often mean eliminating opportunities to make choices, take risks and make mistakes in a safe environment.

“We think, I’m not going to let you make that choice because it’s a bad choice. We don’t want kids to go down the wrong path,” said Phillips. “But when we do that, we are still tying success to a learner being able to do the task and complete the task and not being able to learn from their mistakes. If they do make a choice and regret it, they learn from it. They make a different choice next time. We don’t want them to look to us to make that choice for them.”

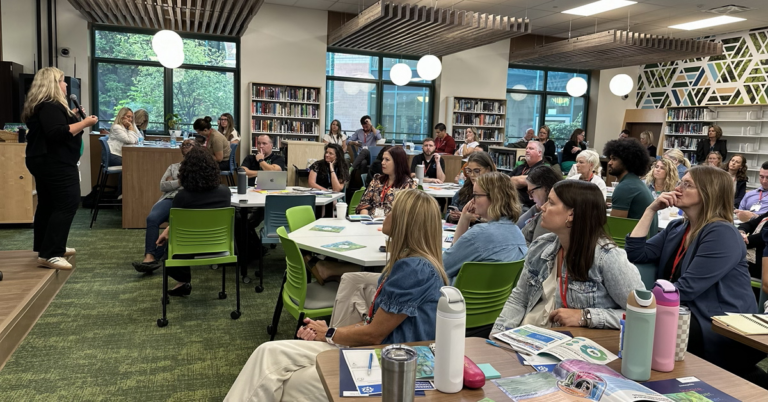

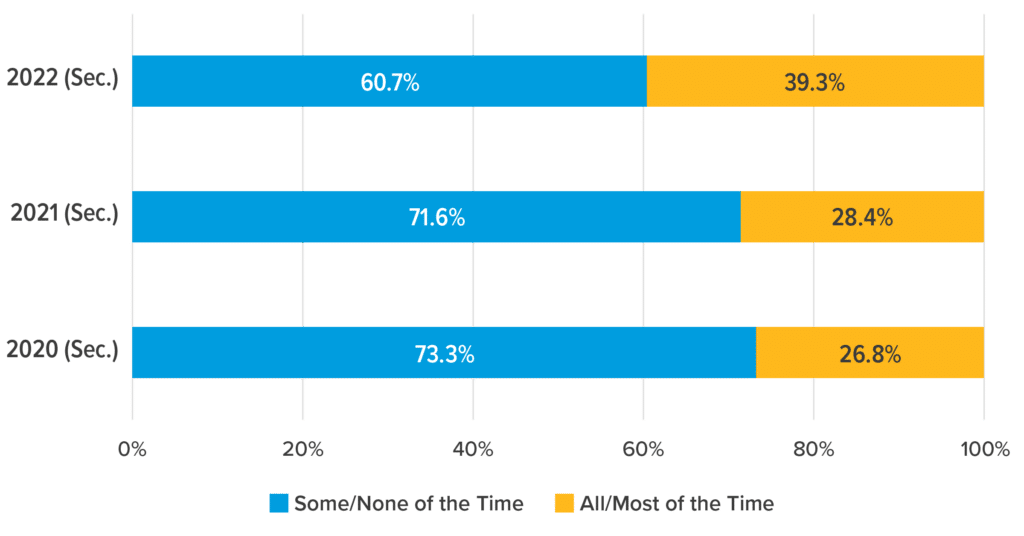

KnowledgeWorks has been collecting survey data from our four partner districts in North Dakota, which includes Oakes. While some educators expressed concern about learners having the discipline and patience to make good choices and take advantage of flexible pacing, confidence is increasing regarding learner responsibility to challenge themselves – and the results show a considerable increase in students reporting opportunities to make choices about their learning.

Learners have choices about how they want to learn.

And it’s not just about their perceptions, but what the power of making decisions and understanding themselves as learners offers students in the long run. In a study of 16 New York City schools, educators were supported in shifting their practices to engage meaningfully with students, soliciting their feedback and, as reported in The 74, “using techniques and strategies that build and leverage their connectedness to their studies and sense of belonging in the classroom.” As teachers changed their approaches, student outcomes improved:

Overall, in the schools where Teaching Matters has a presence, 62% of students met their growth goals on either iReady or NWEA’s Map Growth assessment for the 2021-22 school year. Historically, 50% is the national average for Map Growth. And when looking at iReady’s grade-level metrics, the 16 schools saw the percentage of students at grade level increase from 17% at the beginning of the year to 29% at the end. This illustrates that more students may meet their learning growth goals when educators purposefully adapt and adopt instructional practices in response to their feedback.

This shift in mindset for learners is just as important for educators – and it’s an agency building opportunity for everyone. An educator who believes in themselves, and is vulnerable to making mistakes, creates space for learners to believe in themselves and take risks, too.

“You can’t have a room led by a fixed mindset that fosters a growth mindset,” said Dobitz. “If the educator is not willing to try and fail and learn and remaster and re-envision, then the kids are definitely not going to do anything like that.”

Dobitz supports and encourages the educators in his building to be open to feedback and failure, whether that’s through a site visit or through establishing lines of communication for learners to share their thoughts. For Dobitz, “we have to be okay being observed and learning from others.”

This was written by former Senior Manager of Communications Jillian Kuhlmann.