Teachers are more critical then ever in a personalized learning environment where relationship-building and trust form the foundation for everything that happens in the classroom.

In a personalized, competency-based classroom, teachers are moving between groups of learners, facilitating discussions, helping students explore and set goals, or may be engaged in more direct instruction with a few students at a time. Their classrooms may offer flexible seating and students participate in decisions about how and where they learn. They may be working independently or grouped based on what they’re working on.

Just as the teacher supports their students to take risks and try new things without fear of failure, they’re supported in turn by district leaders who foster a collaborative school culture. Everyone is working together, every step of the way.

Because this classroom looks so different, many teachers – and students, parents, school leaders and community members – still have questions about what teaching and learning in a personalized learning environment looks like.

What’s the difference between teacher-centered and student-centered classrooms?

In a traditional, teacher-centered classroom, teachers ask questions and students answer. Teachers choose what students will be working on and when and deliver direct instruction, often to the whole class at once. Conversely, in a student-centered, personalized classroom the teacher works with students and has the resources and supports that they need to take risks and follow their students’ lead.

In a literacy lesson, for example, a teacher may work with a small group of students whose assessments show they need support in the same skill area, while other students work through learning stations with tasks designed to strengthen their learning. Students benefit from individually-paced, targeted learning tasks that start from where the student is, formatively assess existing skills and knowledge and address the student’s needs and interests.

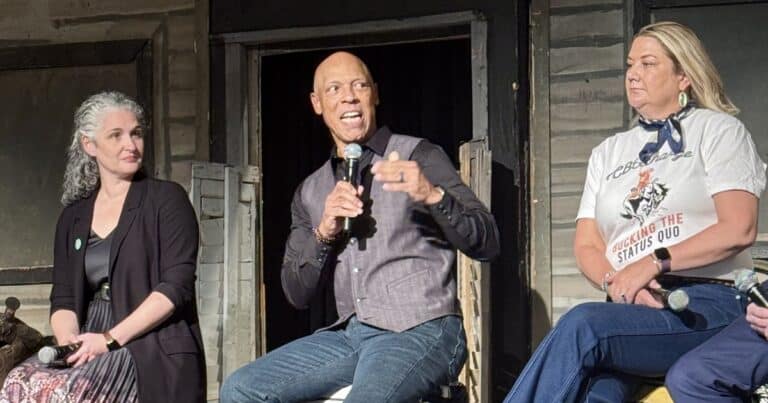

"We have to ask ourselves as educators: How do we teach students to be critical thinkers and writers and have their own voice that a computer can’t duplicate? How do we teach them how to have a positive interaction with an AI? Whether the machine is a factory line 100 years ago or an AI today, we have to teach them to use these tools as tools – not as a replacement," said 2024 Nevada Teacher of the Year Laura Jeanne Penrod. "If AI can write a paper, then I’m not going to have you do a paper. I’m going to have you do a presentation or teach us something that utilizes your creativity, your humanity. We are not creating factory workers. We have to have conversations about teaching children to be irreplaceable."

What does classroom management look like in a personalized, competency-based environment?

The idea of students choosing how they learn, how they show you what they’ve learned, working independently or grouping and regrouping throughout the day, might sound messy to teachers. But the student who feels trusted and has ownership over their learning is a more focused and productive student. Learners also have ample opportunities to practice those critical social and emotional skills that will serve them well in the future when they can recognize their own role in enriching the learning environment. Teachers are still responsible for the class, but when students build a community together, deciding on classroom rules and similar procedures, they hold themselves and each other accountable.

In an elementary classroom, students may decide as a class on an appropriate way to handle classroom materials such as markers or scissors, whereas older learners may decide on how long they have to revise an assignment. These rules still exist – but they are decided upon and enforced by the community, building student agency and ownership.

“I really wanted to be in charge of my classroom,” said Hillary Weiser, a kindergarten teacher at Navin Elementary School in the Marysville Exempted Village School District in Marysville, Ohio. “But I’ve learned to let the kids take charge of their own learning. I have no discipline issues this year, and I don’t think it’s anything I’ve done. This classroom is theirs. They take ownership of what happens here.”

Does personalized learning mean teachers create personalized lesson plans for every student?

Personalizing learning doesn’t mean writing 30 different lesson plans for 30 students, but rather cultivating in students an understanding of themselves as learners and turning over some of the work to the students themselves. Transparency about learning expectations is also key in a personalized, competency-based classroom – if students are aware of their learning targets and what they need to do to demonstrate mastery, learning isn’t a mystery.

In a science class, for example, a teacher may share out at the beginning of the unit the learning targets that each student will need to meet, and work with each student to design the assessment that allows them to demonstrate mastery – whether that’s writing a paper, delivering a presentation, taking a test or something else.

"The majority of our teachers and those who support them are in this realm of getting students more actively involved in their learning,” said Megan Padilla, Santa Cruz Valley School District #35's teaching, learning and assessing director. “We acknowledge our students have different needs, but it can be overwhelming. How do I help everyone? But if we teach students to advocate for themselves and identify when they have a need, that’s a great start. We’re giving them tools. We’re in partnership with students and teachers in identifying those needs. We don’t want to burn teachers out while we’re doing this. When we build systems for learning, we’re getting students acclimated or adjusted. You’re systematizing things in the classroom, getting students to do more of that work."

How do teachers support each student’s individual needs?

To truly personalize learning, teachers must have the support and freedom they need to understand and support each child holistically. Whether it’s a unique family situation, a different culture than their own, poverty or trauma, teachers must have the flexibility to meet their students’ needs in creative and appropriate ways.

Many teachers use data notebooks with students as a way of involving the kids in goal setting and progress monitoring. The notebooks can also include learner profiles, where students set goals and reflect on the ways in which they learn best. “Do I learn my math facts when I am using flashcards or working with a partner?” “What do I need to do my best on this task?” Making the most of the data notebooks can also support a classroom culture that encourages growth mindset: approaching new tasks and skills as an opportunity to learn and grow rather than assuming skills are predetermined.

When personalizing learning, there is a necessary cultural and systemic shift throughout a learning community that brings inequitable practices to light and has the potential to empower teachers to take action and alleviate those inequities. This may require tough, but necessary, conversations about how to serve each child well.

“Personalized learning really requires us to spend a lot of time getting to know our students, what drives them, what motivates them,” said Kimberley Lawson, a seventh and eighth grade English language arts and geography educator with Lexington 3 in rural Batesburg-Leesville, South Carolina. Relationships are central to a personalized, competency-based learning approach, and Lawson sees the impact it has on her students. “Somebody cares about you here,” said Lawson, who explained that when students begin to understand that, “they don’t want to disappoint that person.”

How will assessments work? How will teachers determine if a student has demonstrated mastery?

While end-of-year summative assessments are still a reality for schools, teachers in a personalized learning environment must be comfortable with frequent, embedded student assessments that are closely aligned to instruction so that results can quickly translate into supports for students. These embedded, formative assessments also naturalize the process of assessing progress. Rather than seeming punitive, assessments become a regular touchpoint for both teachers and students to get a pulse on what they know and what they don’t know yet. After an assessment, students can also chart their own growth and set their own learning goal, determining what they will do to reach their goal and what they need their teacher to do. They own their learning.

“They understand better what the concept behind their grade is,” said Yuki Carrillo, a third grade educator who has been teaching at Calabasas School in Santa Cruz, Arizona for 18 years. Since 2019, Santa Cruz Valley School District #35 has been working to shift the way it thinks about student achievement and grades as they work to integrate personalized, competency-based learning into district-wide strategies. This includes a move towards competency-based evaluation and standards-based grading. “Instead of a student having a 90 or a 70 percent, a B or a C, the proficiency scale we use is more specific about what things they need to be moving on, what they’re learning and what they need to practice more. I think the parents saw that their own kids have ownership over what they are learning.”

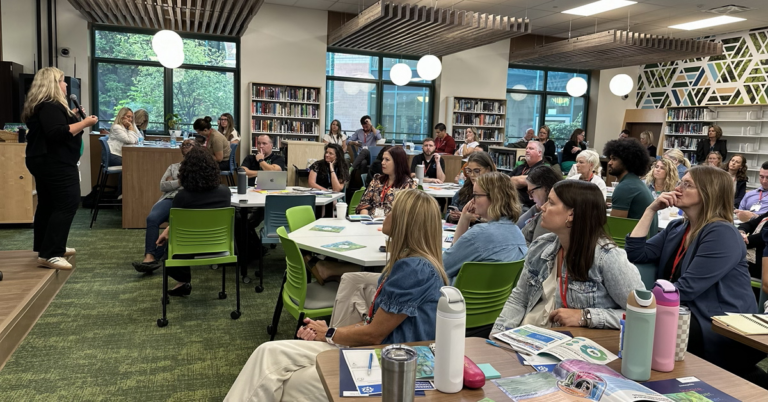

How does personalized learning change the nature of professional development?

Rethinking annual professional development to explicitly support a teacher’s confidence and the development of strategies for personalized learning is critical. Most educators weren’t trained in personalized learning strategies but are excited at the prospect of having more freedom to meet their students where they are. Growth mindset and comfort with failure as a part of the learning process is something that teachers must cultivate in their interactions with students, and it’s made possible by feeling that same support from district leaders and administrators. Teachers need to feel that they are trusted and that if they try something new and it doesn’t work out, they can revisit and adjust.

When asked why it’s so important to be able to learn from other educators and district leaders implementing personalized, competency-based learning, Shawn Wehrer, chief academic officer with Yuma Union High School District in Arizona, likened it to being a new teacher. “When you first become a teacher, you go to other teachers to help you and get different ideas. You’re seeing what other people are putting into place that align with what you’re trying to do,” said Wehrer. “Sometimes you like it and use it. Sometimes you don’t. But you can learn a lot from people you aren’t sitting with every day.”