The nation’s current education systems leave young people unprepared for life after school and concentrates opportunity to a select and predictable few. Too much of a student’s success can be predicted by their race, economic position, ZIP code and other markers of identity. Long-standing disconnects around the purpose of education, varied levels of investment, approaches to instruction and expected outcomes have all contributed to a growing chorus across the nation on what to do next: we must build systems that center learners and their communities.

We can learn from student-centered learning communities as we seek to evolve our school quality systems and ground them in common goals and flexible approaches to improvement.

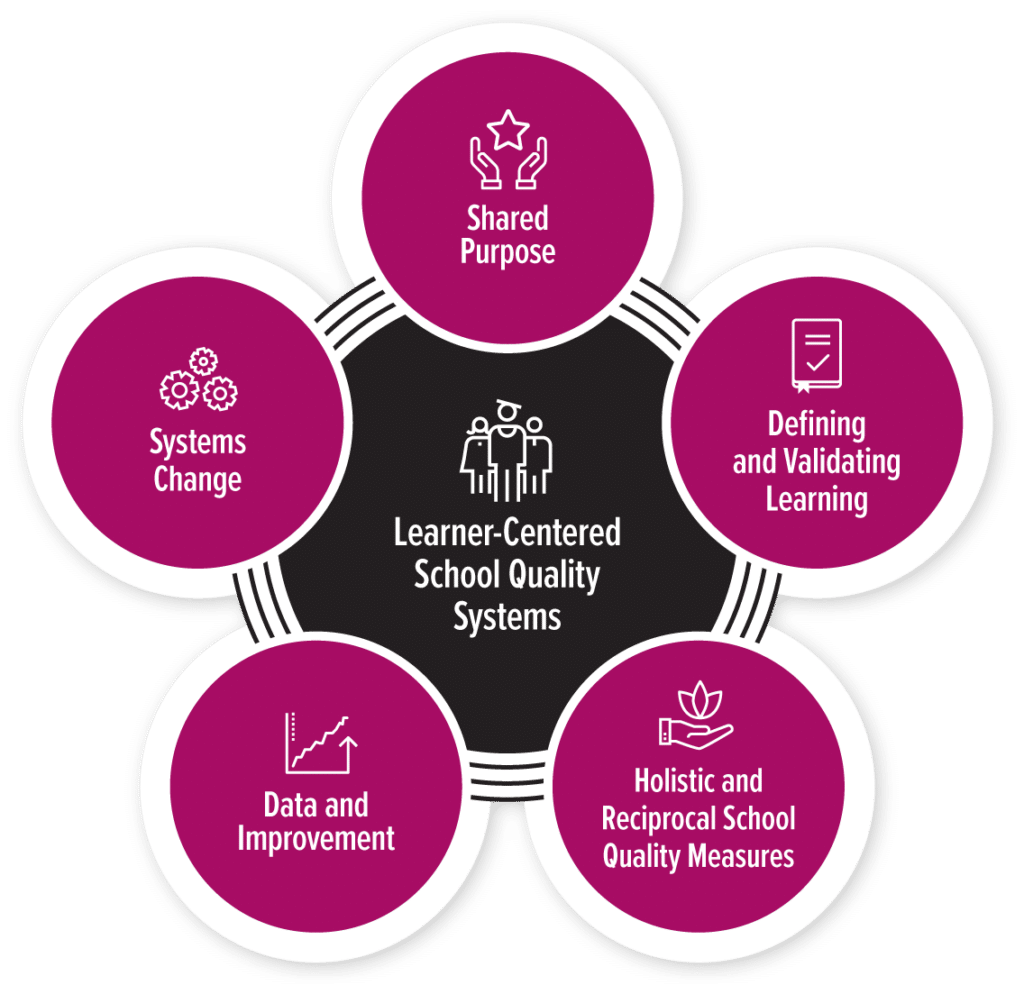

Our bold new vision for assessing school quality honors the unique context of each learning community, while also ensuring the quality of every learner’s experience. This vision is articulated through five themes for transformation and includes recommendations to our nation’s leaders for setting the course for the future of assessment and accountability.

Widespread adoption of student-centered school quality systems will require transformation at each level of the system, from support for those closest to the classroom and ending with federal policy. Alignment of these systems with clear roles and a shared commitment to student success can have a transformative impact on the U.S. K-12 education system.

In Beyond the Horizon: Blazing a Trail Toward Learner-Centered School Quality Systems, learn more about the identified transformation themes, key strategies toward achieving them and policy concepts to explore. See the start of a learning agenda to enrich the design of future policies and systems focused on school quality.

Helping education constituents navigate today’s shifting landscape with resilience and success

KnowledgeWorks recommended short- and long-term actions for the new administration in four key areas

Research tells us assessments in traditional education systems aren’t working. Explore how states can work with the federal government to…

A future of learning where students of all races and ethnicities, incomes and identities pursue the kinds of learning experiences that enable them to uncover their passions and thrive in an evolving world.

Subscribe to receive email updates including expert insights, success stories and resources.