Empower youth with systems thinking tools to take to their learning communities. The following conversation between Katie King, director of strategic foresight engagement at KnowledgeWorks, and Trevor Hicks, seventh grade history teacher at Kairos Academies in St. Louis, Missouri, explores the ways in which youth use systems thinking tools to see the big picture and address community problems, such as youth homelessness, structural racism in schools, gun violence and educational inequity. Watch or read the transcript below.

King: Thanks for joining, Trevor. So we wanted to talk with you as it relates to our systems thinking guidebook, because you have a lot of experience that people have been asking us about, and so we’d just love to hear some of that experience and some of your stories, because you’ve used systems thinking as a way to help students and young people grapple with and take action on issues of racial injustice. I’d love if you could just tell us a little bit more about those experiences, and why you think systems thinking is a useful set of mindsets and tools to do that kind of work with young people.

Hicks: Yeah. So I can talk on those experiences. For the past four years, has it been – not including this summer, unfortunately, because of our circumstances – I’ve worked with the Social System Design Lab at the Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis to host the Changing Systems Youth Summit. And all that is: it’s just both a fellowship and a summit. So there was a three-week fellowship with chosen fellows who apply and we teach them systems thinking and system dynamics and teach them how to facilitate those conversations with their peers. Then, the culminating event is a three-day summit where the fellows, who we train are teaching their peers with these tools, are typically tackling a problem that they see are facing their community. So we’ve had problems of youth homelessness, structural racism in schools, gun violence and educational inequity.

So my experience has just been guiding those fellows, teaching them the tools and really helping them see the value in their voice and their expertise based on their experiences. I never walk in the room and say, “I’m an expert on gun violence, and I’m going to teach you everything there is about gun violence.” It’s more so that I’m a facilitator, and we’re going to pull out your stories and your experiences and see what the system looks like to us and where could we possibly intervene based on how we see the system. The goal is to have as many voices in the room as possible, so we can start to build that picture a little bit more. That’s been my main experience with using these tools with youth.

Looking Beneath the Surface is a guidebook that introduces education stakeholders and changemakers to the theories, language, mindsets and tools of systems thinking for the purpose of informing approaches to systems change.

Read now >

King: And what would you say are some of the things that have come from that – insights that they have come to, actions that they’ve taken, some of the results of those conversations and using these tools that they may have had?

Hicks: Some of the major high-level insights that we’ve seen is: Students typically walk away with understanding; they see the bigger picture. So before they had this very narrow vision of what youth homelessness or gun violence or educational equity or racism looked like. They have this very narrow lens. And after being around their peers and walking through these tools and exploring and diving into what the system looks like to other people out there close to their age, they start to see that “my experience is valid, but other experiences are also valid.” And those experiences really paint a bigger picture for those kids.

What I’m trying to say is that there’s that bigger picture understanding. So they still have their own mental model of it, but then now they see other’s point of views, so they can start to consider those and think about, “Okay, well, if I experienced this and you experienced this, how can we come together to find a solution that works for both of us and can also change the system to the best of our ability?”

King: Why do you think systems thinking is a good approach for those kinds of conversations in that sort of outcome? I feel like there’s so many different ways to collaborate, and different ways to have conversations. What have you seen as unique or particularly powerful about systems thinking?

Hicks: I think it’s a very unique set of tools, and conversations can spark from it, because it’s not a traditional way to talk about a problem. I wish it would become the norm, because that would be amazing. But until then, it’s very non-traditional, from my experience and just talking to other people who aren’t familiar with it. But I think what it is is that no one in the room is an expert, and telling our own stories and bringing together experiences that can help you paint the bigger picture of this system, really help students see, “Wow, I now see the bigger picture of the world, that there’s so much going on here. I didn’t even know about these things because I’m not affected but so many other people are affected by it.”

I think it’s just an effective way. And it’s subjective, but it’s also objective at the same time. It allows people to step back and put their brain on a piece of paper or a chart or whatever, and they can see it and they can tweak it with whoever they’re working with. Typically my work is done in groups, so they can work together to figure out: “No, this doesn’t fit right. This doesn’t really tell the picture of this story.” It’s very story-centered, and I think that’s the biggest part of it because you can do a lot of learning from stories and learning about other people’s experiences. And to me, working with systems and youth, especially, their stories help each other see bigger pictures, see the system a little bit more clear, and also them too, because they get the sense of, “Wow, my experiences are valid. People listen to my stories and my stories are real.”

Because sometimes as youth – I remember growing up – sometimes my voice always wasn’t considered when it came to speaking to adults, because I’m a junior in high school; what do I really know compared to what someone else might know? These tools really empower students to really think critically but also be advocates for their own education and for their own voice. They use that voice to create the change that they want to see in their school or community or wherever they want to see that change.

King: Yeah. I think it’s interesting because systems thinking treats your experience in the system as an important data point.

Hicks: Exactly.

“These tools really empower students to really think critically but also be advocates for their own education and for their own voice. They use that voice to create the change that they want to see in their school or community or wherever they want to see that change.”

King: That’s your story, but that’s something that needs to be put down on paper and needs to be considered in the whole picture – which is validating. It allows us to really find the truth in that, and that matters when we’re thinking about problems and solutions that people experience in a system are as important to consider as the rules and the policies and the funding and all of the things that go into the system – that the experience is another variable that we have to think about.

Hicks: I think another important aspect of, and the reason why I think youth grab onto it so much, is it doesn’t feel like we’re just sitting around in a circle talking about the problem itself. We’re physically trying to problem solve at the same time or not, is what I perceive youths to feel like. Yes, we’re talking about this very heavy issue of racism, but at the same time, we’re telling stories and we’re drawing these maps and models and it feels a little more interactive and hands-on. And then at the end, the students step back and they see their final product like, wow, it didn’t feel like we did all this, but we really dove really deep into what’s going on in our community, for instance. Something about that hands-on tactile learning and exploring, I think is really powerful for youth, as well.

King: Do you have any particular memory of either an action that a group took after coming together in this way, or maybe an “aha” moment that they had about their system or their school that came about as a result of doing this kind of work?

Hicks: I think some of the best examples I can use are when you’re hearing little bits and pieces of stories of students going back to those schools and becoming advocates and fighting for the change they want to see in their schools. No super specific story for that example, but students will come back the next year either as a participant or as a fellow again, and they’ll talk about, “We tried to start this initiative at school. The administration wasn’t listening; our teachers weren’t listening, but we kept pushing and kept fighting and showed them this is how the system kind of works from our perspective. And this is the change we want to make, and sometimes that works in the school; sometimes it doesn’t.”

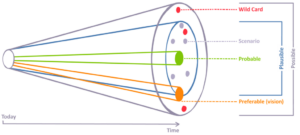

The future has the potential to unfold in many ways and exploring those possibilities can be overwhelming. The cone of plausibility is one tool that can help guide explorations of plausible, probable, possible and preferred futures.

Learn more >

I think some “aha” moments I’ve seen are for students, when it just clicks all of a sudden. Honestly, the tools we’re using click, because sometimes it can be a little intimidating, but also the issue or the problem we’re tackling, it just starts to make a lot more sense to students. I remember gun violence specifically, a student said that when he thinks of gun violence, he just thinks of someone with a gun in their hand, pulling the trigger. But he said, when you dive into the system dynamics of it, there’s a lot more reasons, and there’s roots to why people put a gun in their hand in the first place. That’s one really vivid memory as to an experience that I have where a student had an “aha” moment.

But just those little bits and pieces and little impromptu conversations that I have. It’s such an empowerment tool. I’ve seen some of the high schoolers that I worked with go off to college, and they’re just doing amazing in college. They’re all involved on campus, advocating for the changes they want to see on their campus. To me, it’s just a tool. For some, it’s a means to an end. For others, they take it and use it. But at the end of the day, I think what it really does is just empower students to use their voice and be the change they wish to see. I know that sounds kind of cliché, but that’s-

King: I mean, it’s a cliché for a reason.

Hicks: Yeah.

King: And I appreciate the way that the Waters Center, which we have both worked with, frames it as habits and mindsets, that you do these processes and you use these tools, but it’s when they start to click and they start to influence the way that you think, and the way that the lens through which you see the world, that’s when it really can become powerful. Having that experience at a formative time in high school, or even younger, really makes a huge difference to how people see problems, approach problems, work together.

Hicks: And we always can’t measure that too, because you can’t always measure habits and mindsets, unfortunately. But from my experience, because I started systems thinking and doing the system dynamics work in high school, my junior year I believe, and continued it through college. And then, even up to before teaching, I was working with an organization that did a lot of system dynamics. Transitioning to a teacher role, all I can see is systems, the systems that affect my students and me as a teacher. It really is like a mindset shift, and they become habits. The way I have conversations with other teachers about just planning and what we can do for our students, honestly, it’s shaped who I am. It’s shaped who I am. And that’s the reason I’m on this call, because it has shaped who I am. It has led me to a lot of experiences. And I know that I’m not the only student who’s gone through it and has changed because of it.

Creating systems diagrams involves learning and reflection. See how mental models can change when taking systemic racism into account.