Silver Anderson is pursuing a degree in architecture and environmental engineering because she believes “there is a delicate balance between human needs and environmental concerns, and it is our responsibility to manage the complexity of our lives within the potentiality of our environment.”

She explained this in her senior capstone, a project that serves not only as a place to assert her goal but also to highlight her skills, illustrating the ways she has met the Northern Cass School District’s Portrait of a Learner by reflecting on how her experiences both in and outside of school demonstrate accountability, communication, adaptability, a learner’s mindset and leadership.

“We’re really looking at the body of experiences a kid has, and how we can pull those together,” said Tom Klapp, director of personalized learning with Northern Cass. “Content is important, but we really want to get kids thinking about the skills we want them to have first: What can I do to work on that skill, to grow in that skill and eventually be able to show it? Our kids are growing up in a world where information is readily available and our job as educators is to teach them about what we do with that information, how we apply it.”

The Portrait of a Learner, sometimes called a Portrait of a Graduate, is a tool increasingly used by K-12 school districts to identify those skills, knowledges and dispositions their graduates will need to succeed in an uncertain future. From there, districts can identify meaningful measures of success, because what we measure matters – but so does the how and why behind those measures.

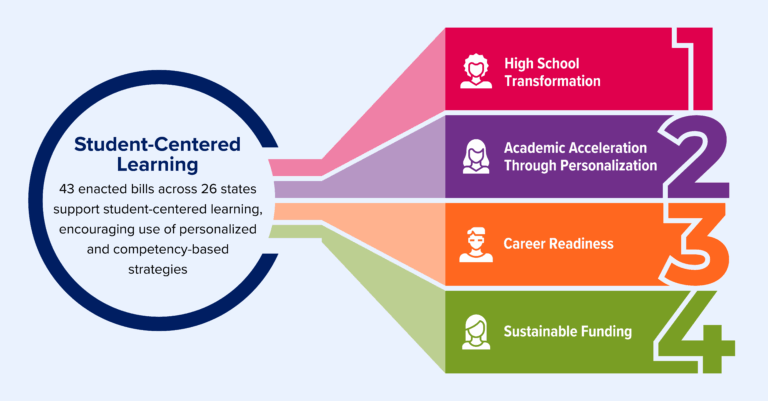

In Finding Your Path: A Navigation Tool for Scaling Personalized, Competency-Based Learning, we identify 12 conditions necessary for learning communities to navigate systemic change. A big part of quantifying this work is through observing and capturing the spread of student-centered practices within a given school district or building. Connected to the 12 conditions are eight student impact areas:

- Student Agency

- Supportive Relationships

- Positive and Equitable Learning Environments

- Shift to Competency-Based System

- Deeper Learning

- Equity of Learning

- Career Readiness Skills

- Post-Secondary Outcomes

“We’re helping schools and districts prepare each student for their future. That calls for a mix of robust measures of learning that are student-centered and equitable to indicate progress in classrooms and systems,” explains Rebecca Wolfe, vice president of impact and improvement at KnowledgeWorks. “We can’t ask schools and students to transform learning but then measure progress with outdated, limited and biased methods.”

Future-focused measures like the skills, knowledges and dispositions outlined in a Portrait of a Learner – and how those are being realized in Megan Margerum’s third grade classroom.

“My passion is making sure that we are incorporating the Portrait of a Learner concepts at a young age,” said Margerum, a third-grade teacher with Northern Cass. “How can we incorporate these words into their day-to-day work – accountability, communication, adaptability, a learner’s mindset and leadership – and help them learn how they can show evidence? Kids as young as preschool can do that. It’s just so important because these are the things that they’re going to have to do, and be, and be able to show. It encompasses everything we need to be as a citizen in this community.”

In addition to projects that incorporate the Portrait of a Learner, Margerum’s students discuss how people and characters demonstrate the Portrait of a Learner words and engage in historical studies of individuals who have shown themselves to have these qualities. Margerum works to point out to her students when they are conferencing with her, for example, how they are utilizing their communications or accountability skills, among others. She also models what it looks like when she hasn’t used certain skills well.

I think my learners will love our new way of keeping track and interacting with all priority standards. @NCSD97 @knowledgeworks @NDCELorg #prioritystandards #powerstandards #education #personalizend #personalizedlearning pic.twitter.com/yZFWLicSdA

— Megan Margerum (@MeganMargerum) February 10, 2022

“What I want to instill in my kids is that if you ever feel you’re at a point where you’re done learning, you aren’t there. We’re always learning,” Margerum said. “My kids know that this is a safe space where they can make mistakes, where they can see me make mistakes.”

While Margerum is working to ensure her students have a clear understanding of what each of the words identified in the Portrait of a Learner mean and how they can show they’re practicing the skills those words describe, the district continues to grow in the ways they are centralizing these skills.

“People, by and large, agree that the world is a different place; it’s changing exponentially,” said Klapp. “We don’t know what graduates are going to be asked to do four years from now or eight years from now. But what we do know is that there’s a set of skills that it takes to succeed. Those skills have been true for the last 100, 200 years: to be a self-autonomous learner, to be able to communicate, collaborate, to be self-driven. When school hasn’t changed at all to adapt to a changing world, it’s time for us to make that change.”

When school hasn’t changed at all to adapt to a changing world, it’s time for us to make that change.

Why student agency and ownership of learning matters

Northern Cass students and educators are among those contributing to data in KnowledgeWorks research into student impact areas – and we’re taking a similarly long view. While survey data, interviews, focus groups and observations provide insights on each of the student impact areas, they are organized by time horizons, as well, to demonstrate when learning communities can anticipate having measurable progress – and how that progress aligns to something like a state or district’s Portrait of a Graduate. Student agency, for example, is one of the first areas where a learning community may see measurable improvement. Students feeling a sense of ownership over their learning – that what they do matters and is relevant to the futures they hope to pursue – is critical for the culture shift that must take place to support a personalized, competency-based learning environment.

“We’re asking questions that get at the structures that need to be embedded within a system to build student agency,” said Drake Bryan, director of continuous improvement at KnowledgeWorks, stressing that showing growth is the goal. “For example, we ask students how often they work with their teachers to determine when they’re ready to take a test. In 2020, a third of the students who responded to our survey in North Dakota said that they could do this. In 2021, we saw a 7-percentage point increase. That’s a big leap.”

Deciding when they’re ready to take a test is an example of student agency, and this kind of agency can only be achieved if school structures allow for it. Until structures like learning pathways – which provide learners the flexibility to move at pace, co-design learning experiences and assess when ready – are built, there’s only so much student ownership and personalization of learning.

We already have two years of quantitative data and three years of qualitative data in North Dakota and are actively collecting data in Arizona and South Carolina, as well. We will be sharing our findings with the states to help learning communities better identify where they want to focus their efforts and how we can support them in achieving their outcomes.

Virgel Hammonds, chief learning officer with KnowledgeWorks, is candid about the different ways we’re helping districts build their capacity and use data to engage in continuous improvement.

“As a result of the work that’s happening in North Dakota, we are accelerating and creating greater impact. For example, we’ve worked with states on the identification of a statewide Profile of a Graduate to create a visual representation of shared goals,” said Hammonds. “It’s not strictly on high school educators to make learning growth and success a reality. It’s for all of us, preschool through high school. We start to think about what structures or processes we need in place, how our roles might change, how do we support it with data if we’ve all been a part of identifying what we want for graduates. It inspires greater partnerships.”

Changing the conversation about transcripts and college admission

While we continue to work with learning communities and states on supplemental measures for showing growth, organizations like Mastery Transcript Consortium (MTC) are partnering with districts and higher education institutions to ensure things like the Portrait of a Graduate are paired with a transcript that goes beyond standard measurements to truly illustrate what a student knows and knows how to do. According to the MTC website, a “digital high school transcript that opens up opportunity for each and every student — from all backgrounds, locations, and types of schools — to have their unique strengths, abilities, interests, and histories fostered, understood and celebrated.”

Every college or university that receives a mastery transcript is sent information about how to access and interpret it and invited to a one-on-one conversation with MTC. The goal, however, according to MTC’s Chief Education Officer Patricia Russell, is to pivot the conversation away from college admissions staff just dealing with transcripts one at a time.

“Many college admission folks have expressed strong support for the Mastery Transcript even as they ask how they will pivot from an admission system built around some age-old and fracturing assumptions around course titles, grades and standardized test scores,” said Russell. “As use of the Mastery Transcript expands, colleges may need to redefine their admission criteria to focus on a list of clearly defined competencies needed to be successful in the college program. An admission reader can then readily determine if an applicant is qualified based on the competencies (with supporting evidence) on the Mastery Transcript.”

For Hammonds, tools like the Mastery Transcript are essential to changing the conversation about success and how we evaluate and report, especially as more states review and adapt their accountability measures.

“When a state has something like a statewide Profile of a Graduate, we have schools asking, ‘How do we make this a reality?’ It means we may have to change a lot of our infrastructure, our reporting process, our transcript process,” said Hammonds. “This is an opportunity to think about how we connect and partner and answer these questions for our learning communities. They’re transforming not just for K-12, but for a lifetime.”

COVID-19 provided states the opportunity to accelerate their progress in rethinking state assessment systems to ensure they support the individual learning of all students. Learn more about how 14 states are continuing to make progress in rethinking system accountability and K-12 assessment systems.

Read now >>

A small but growing number of schools and districts that MTC partners with utilize the Mastery Transcript, though many others use the organization’s resources to track growth toward competencies, capstone projects, student-led conferences and exhibitions of progress, among others. For these tools and for the transcript, students curate and submit evidence, and teachers review.

“You want to be able to highlight those experiences and skills mastered that go deeper than others – maybe give the student an opportunity to do something they wouldn’t have been able to do in a traditional environment,” said Susan Bell, senior director of member school engagement with MTC. “You want to give them the opportunity to create that story that shows who they truly are.”

Hammonds likens the process to crafting a resume, a cover letter or building a portfolio as a job seeker.

“You want to be able to give your best evidence. Kids can do that, too,” said Hammonds. “Traditional transcripts don’t provide any of that evidence.”

Scaling personalized, competency-based learning requires alignment between states and learning communities.

For Bryan, helping states and districts align what they collect and why is critical. It’s what moves us from having small pockets of success to transformation on a larger scale. It’s great if one community is doing better, but if the neighboring district isn’t seeing those same successes, we’re creating larger inequities rather than opportunities.

“We can collect as much data as we want at the district level, but until states have prioritized the collection of more meaningful, personalized learning data that aligns to their goals, it’s hard to capitalize on and spread isolated success,” said Bryan. “It’s important that states have a better understanding of what they want and how to measure that, how to know if they’ve achieved it or haven’t, if they’re making progress.”

And that statewide progress begins in schools, in classrooms, with learners.

Margerum wants to help make the growth she’s seeing and experiencing a reality for her peers in a way that helps shape how each student is connecting to the district’s Profile of a Learner.

“I try as a teacher leader to excite others about this work, to look together at all the big things that we do throughout the year that our learners are going to remember, whatever it is, and think about how it’s relevant, and how it’s connecting to the Portrait of a Learner,” said Margerum. “Those are our foundations for our graduates. Let’s make them a foundation in their elementary years, too.”

Designing competencies that align with a state Portrait of a Graduate is a big undertaking with even bigger impact. Learn how Utah educators approached this work.

This was written by former Senior Manager of Communications Jillian Kuhlmann.