“Just as every student has unique skills, strengths and abilities, every educator has unique skills, strengths and abilities, too,” said Jay Haugen, superintendent of Farmington Area Public Schools in Farmington, Minnesota. “One-size-fits-all doesn’t work for our students, and it doesn’t work for our staff.”

The concept of agency – individuals having the ability to make choices, take ownership and share in decision-making – is the defining factor for school culture in Farmington. At KnowledgeWorks, we talk a lot about the importance of student agency in increasing their sense of ownership of their learning, and in Farmington, how teachers feel about their own learning and progress is just as important. We couldn’t agree more.

While the district has been working on implementing personalized, competency-based learning for seven years, district administrators and leaders provide multiple entry points for teachers and they don’t require that anyone comply with any one aspect of their implementation. Beyond the district’s organizing principles and an instructional framework that focuses on a gradual release of responsibility, teachers are supported in finding their own way toward more student-centered practices. There is always some measure of direct instruction, guided practice and independent practice, and educators work from agreed upon indicators of what personalized, competency-based learning looks like, sounds like and feels like. But Haugen insisted it’s not about a set instructional practice, but a way of thinking.

“What we’re after is preserving agency in the whole district, students and staff,” said Haugen. “If everybody can use their natural strengths and talents, good things are going to happen. With all these entry points into personalized learning, it may be that the part about being self-paced naturally resonates for some teachers, or maybe the idea of competency, voice and voice or where and when students learn. But all these practices come together – once you go down any of those roads, you run into those other roads.”

A mindset shift for administrators

“We as administrators had to ask ourselves, what am I making the adults in the building do that’s strictly compliance? What can I free them from?” Asked Jason Berg, executive director of educational services with the district. “We were modeling the process for them: what are you making your students do that’s just compliance? How much artificial conflict did you create? It’s this idea of radical trust in our students, in our staff. We’ve been telling people what to do for 200 years and nothing has changed. We need to honor their agency, let them direct the work.”

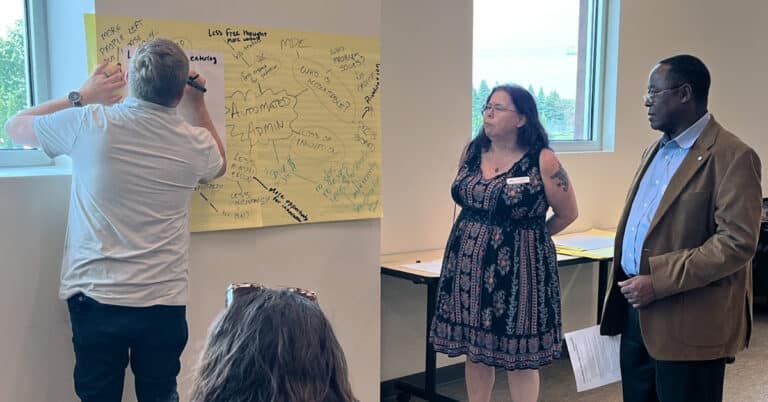

Anything that Haugen and Berg could free their teachers from, they did, including submitting lesson/unit plans, submitting collaboration notes and implementing initiatives. Teachers were provided regular time in every building to collaborate with each other, building on the district-defined ‘why’ for personalized, competency-based learning and figuring out the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ of implementation for themselves with ample administrative support.

“Giving people the opportunity to interact with your purpose and think about how they can bring it alive, connect it to their strengths, passions and interests, it really changes how you think,” said Berg. “It’s not until you change how you think that you can change what you do.”

Each school building was responsible for writing a strategic plan that aligned with the district level plan, identifying those parts of personalized, competency-based learning that really resonated with their staff and going after them. Each educator would then set their own goals based on what was in the strategic plan at their school building.

“It’s kind of like personalizing learning with a student, every kid creates their own pathway. Teachers get the same opportunity,” Haugen said. “Our role as administrators has changed. We’re not leaders so much as supporters. Teachers are the leaders and we’re supporting them in their leadership.”

Professional development tailored to meet teachers where they are

Katie Landers, a kindergarten teacher at Farmington Elementary, appreciates the opportunity to choose professional development based on what she needs to better support her learners.

“Rather than on staff development days having a speaker come in that every single person comes and listens to, we have personalized staff development,” Landers said. “We record what we did and how we choose to use the time. The sky is the limit.”

Lori Phillips, a teaching and learning director with KnowledgeWorks, has facilitated a number of sessions with Farmington educators, including sessions on design thinking, learner agency and academic competencies.

“Teachers are engaged and motivated to learn because it is their choice to attend,” said Phillips. “They decide whether the professional development aligns with their current goals; they’re ready to take the risk and feel supported as they fail forward.”

In addition to being supported in choosing her own professional development, Landers has also collaborated with teachers throughout the districts to use personal learner profiles in her classroom. Other teachers have pursued flexible seating, scheduling and pacing, design thinking, infusion of learner voice and choice and other student-centered practices, or any combination of the above best-suited to the needs of their learners and their own comfort level.

Berg credits some of the progress they’ve made with personalized learning to their willingness to turn control over to their teachers.

“We don’t see compliance. We don’t have people going through the motions and pretending, because they don’t have to,” said Berg, who was a principal in the district before taking on his current role. “Our staff that are working on these things are a level of accountability for it that we could never have gotten out of them. It’s their choice, their work.”

Trusting teachers translates to trusting students

Change hasn’t happened overnight in Farmington, and for district leadership, that’s okay. It’s a process – and as student-centered practices spread, Farmington’s students are becoming their own best advocates, communicating with their teachers about how they learn best and what they need.

“I remember after a year of doing this work, I took a walk around a school building and looked in every window to see the teacher at the front of the classroom and the students in desks in rows,” said Haugen. “Now when I take people on tours, you can’t find a teacher in front of the classroom. Students won’t stand for it. They’ll tell you what they need.”

There was an adjustment for teachers, too, in beginning to own their experience.

“All we ever say to teachers is ‘yes,’” Haugen said. “And now they don’t even ask anymore, because they know they don’t have to.”

For Landers, feeling trusted by district and building leadership empowers her to extend that trust to her students.

“How amazing that I am basically being told that ‘we hired you for a reason, that you have something special to offer that nobody else can,’” said Landers. “You have to get the kids to these standards, but you get to decide how to do it. You have your own strengths. You know how to teach. I feel like that’s what we’re doing with students, too. That’s a lot of freedom. It really empowers you.”

With personalized, competency-based learning, the focus becomes on what students are learning instead of what teachers are teaching. to change this text.

This was written by former Senior Manager of Communications Jillian Kuhlmann.